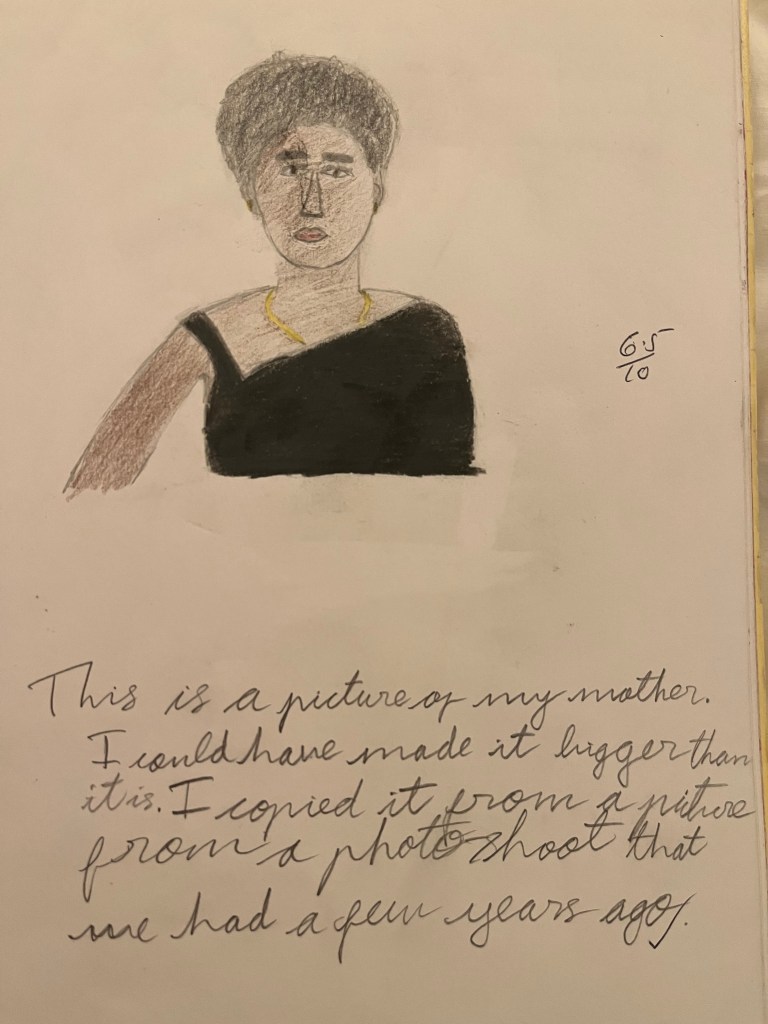

(Credit:: Saagar Naresh. Age 12. Art Homework.)

It’s an ordinary day that starts as the sun peeps from somewhere behind the horizon and ends as it vanishes somewhere behind another at different times for different people on the globe scattered all over these continents everywhere. It is not a singular day as it claims to be.

It’s not my enemy and yet it circles around each year as a reminder of what happened as if I need reminding. It’s not my enemy even though it feels like one. It’s just another day, innocent and ignorant, asking me to sit down. Have another cup of tea.

It was nameless and inconspicuous until it arrived hiding a deep darkness within its light wearing the face of a sacred place and a robe of expansion and growth and holding a promise of transformation before I knew what that meant, unlocking the path to an invisible destination.

This endless path covered in thorns and nettles with no alternative or detour must be trodden with bare feet. It is essential they bleed.

To my desperate open eyes the destination remains invisible. When I let them close I glean a faint ray of hope.