Last night, sleep would not come. As I lay breathing in bed, with my eyes closed, a huge wave of thoughts flooded in, unfurling a surge of all kinds of feelings. Pride. Sadness. Joy. Nostalgia. Everything in between. I tried to focus on listening to the chirping crickets and the silence in between those sounds, the ruffle of the dogs, the incessant mosquito, the rustle of the leaves, Si’s breathing. I tried to recede into the stillness behind these thoughts and invite sleep in that way but that proved to be pointless. It did not want to come. Not yet. The jostling with thoughts went on for a while. It felt natural. It carried on non-stop for about three hours. Luckily, it did not turn into a flight and saved me a lot of energy. I let the body rest despite the mental acrobatics. Even though my heart was drumming in my ears, I lay still. Quiet.

This is possibly what they mean when they say about our final moments – ‘your whole life flashes past your eyes.’ It was not unpleasant. It was natural for it to happen, even though it was an utterly non-consequential happening. It was in anticipation of a big change.

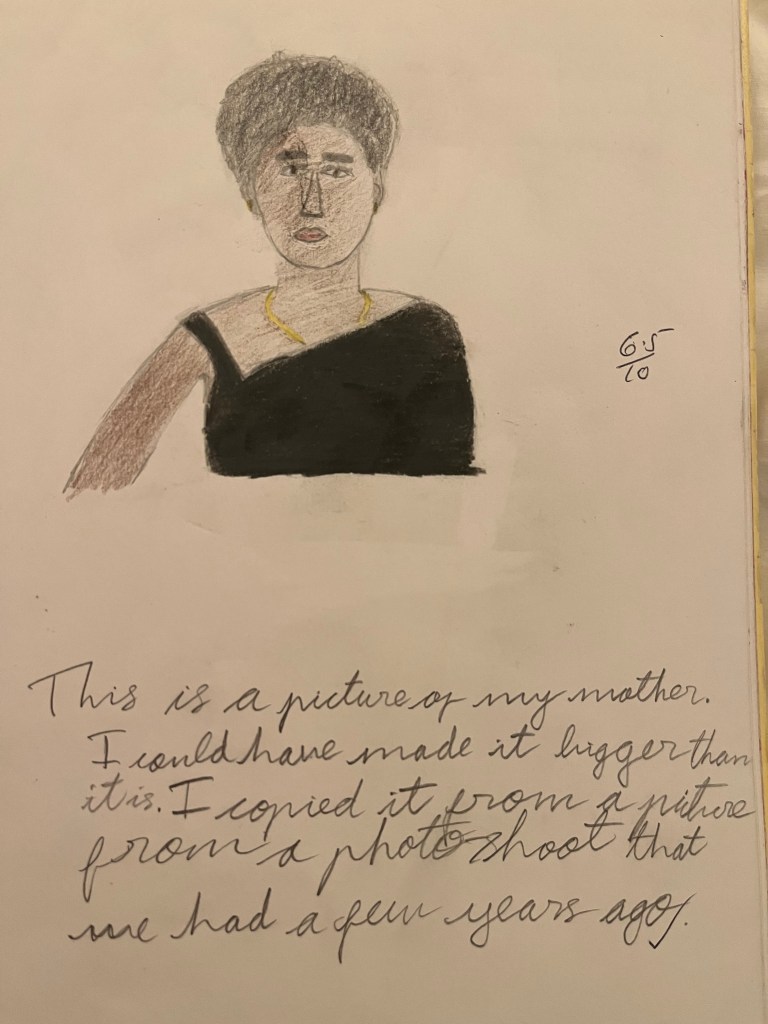

Today, the sale of our UK home was completed. It was ours for twenty years.

No more dinner parties, parcel deliveries, Council tax, gas and electricity bills. No more local library, pub, cafe or cinema. No more knocks on the door by our friends, cleaner or neighbour. No more fire-engine sirens from the fire brigade down the road. No more parking in front of the blue door. No more waiting for Bus numbers 196 and 468.

No more heartache while walking past the GP surgery or the Train station.

The end of an era.

Another letting go.

Another lightness.

Another simplification.

Another freedom.