“More than two thousand people read my post and saw my video today “ Yuval said.

‘They will see it and be moved by it. What then? What will they do?’ asked Basel.

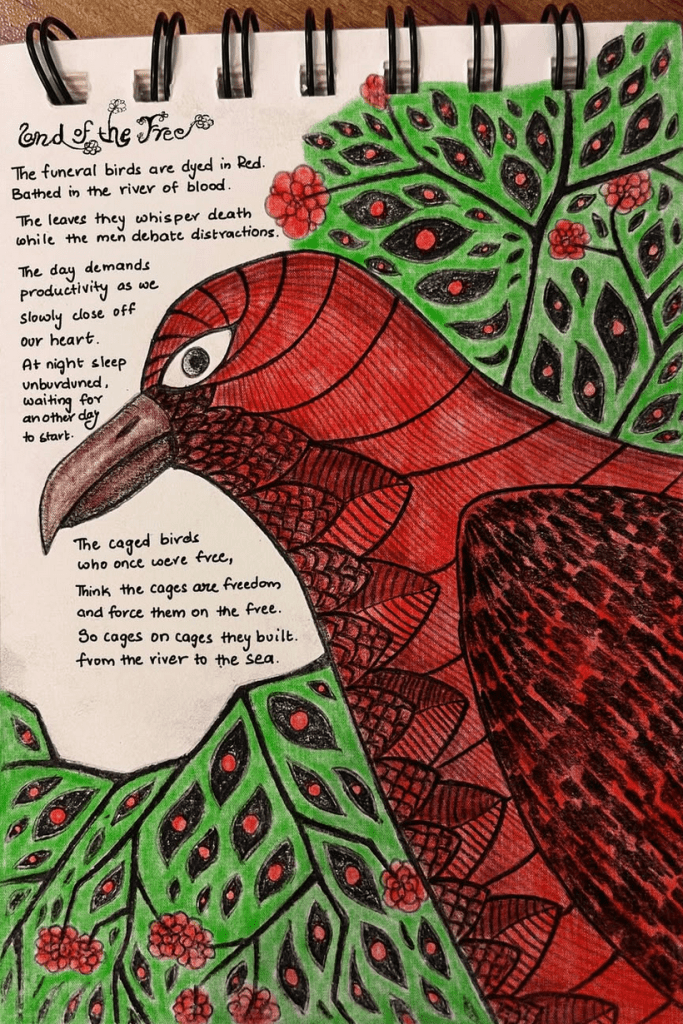

That is the big question. What can we do? What will we do? Two young journalists from either camp came together to document the encroachment and destruction of a village called Masafer Yatta on the West Bank. They raise this question loud and clear for each of us. What can I do? The injustice of all this pushing and kicking, hurting and forcing fills me to the brim with a sense of sadness and powerlessness. My arms and legs go limp. So, thus far I’ve been running away from it. I must be a coward. What can I do? So many influential and powerful people have been quiet, watching the numbers and images get worse every day for decades.

Today, I watched No Other Land on the big screen. Live footage shot on a mobile phone over 4 years, 2019 to 2023. Running away is not possible anymore.

Harun’s mother prayed for his death. This young man was shot by a soldier while he was trying to stop his home from being demolished by the army. The bullet left him paralysed from his neck down. He was nursed in a cave as they had no house. No facilities. No transport. No freedoms. Everything around them was being bull-dozed – chicken coups, elementary schools, homes and villages. No one knew what new destruction each new day would bring. Toddlers were learning to speak, and older kids were trying to play and go to school in the middle of this madness. The respectable Mr Tony Blair graced the village with his pointless guest appearance for seven minutes.

Our world is bipolar, selectively blind. It’s okay for the politics of some nations to be tied to a faith but not for others, it’s okay for some nations to dishonour every treaty that they ever signed but not for others, it’s okay to condemn the exact same atrocities when committed by one nation and not another, it’s okay for third parties to fund and support the killing of women and children in plain sight. This is our world.

We humans have the arrogance to believe we are the smartest of all species, yet dogs don’t kill other dogs in millions every year. No other species has constructed the level of othering that humans have. We can’t see what we are doing to ourselves. We can’t see that there is no other. It’s only us in different garbs. Those of us who can see, must see. Those who can write, must write. Those who can sing, must sing. Let not our dark side win.

Arrogance, blindness and cowardice – a recipe for self-extinction.

By Abdul Raheem (https://www.instagram.com/mud._.lotus)